The Stage 2 building forms and material selection respond and celebrate the passive and active ESD principles, creating a dynamic and pleasing learning environment.

Challenge

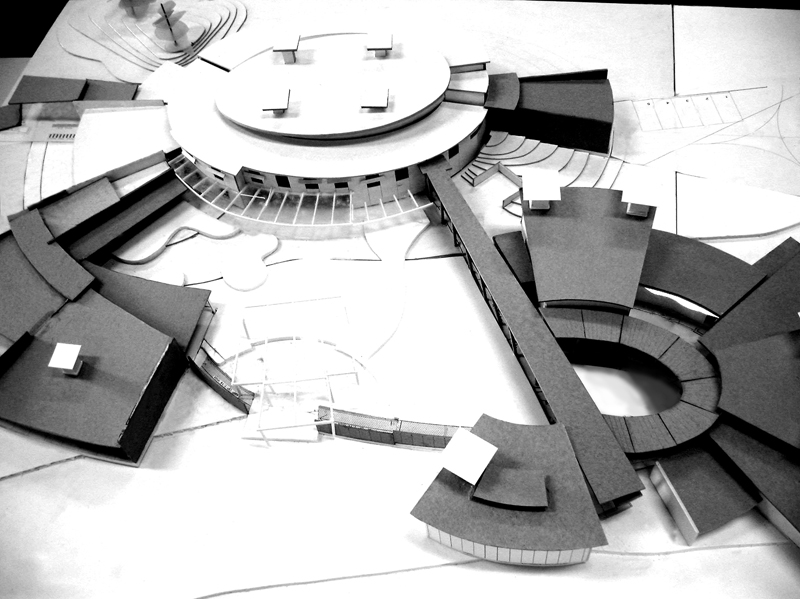

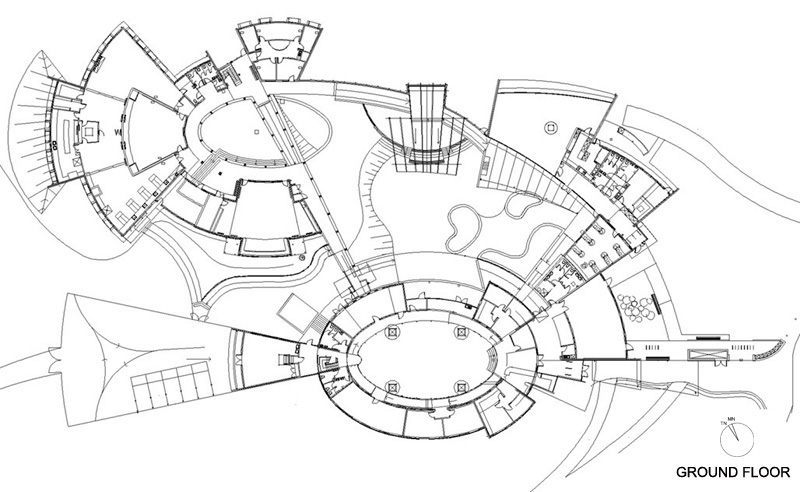

In 1998 the Office of Design (Charles Sturt University) collaborated with C.N. Walton & Associates to design its Interactive Learning Centre at the Dubbo Campus in western New South Wales.

Following the success of this project, the university decided to carry out a second stage of works, and engaged Caroline Pidcock Architects in association with the Office of Design and C.N. Walton Associates to design and document Stage 2 of the Dubbo Campus.

Solution

The Stage 2 works augments the principles of sustainable design introduced in Stage 1. ESD initiatives have included:

- The use of insulated thermal mass to moderate diurnal air temperature fluctuations;

- Orienting the buildings to maximise passive solar design;

- Natural daylighting and ventilation; and

- The introduction of innovative evaporative cooling techniques appropriate to the hot dry climate in summer.

The building forms and material selection respond and celebrate the passive and active ESD principles, creating a dynamic and pleasing learning environment.

Resources

- Simple and intuitive methods for operating the building.

- Collaborative team approach.

- Provision of home office facilities.

- Building designed to be adaptable and accessible.

IEQ

- Good thermal performance of building.

- Good natural light and ventilation.

- Good views to the outside.

Energy

- Good thermal performance to result in minimal heating and cooling.

- Appropriate levels of insulation and thermal mass.

- Ability to zone areas of the building.

- Well designed natural ventilation throughout building.

- Good natural light throughout building.

Water

- High performance water saving fixtures and appliances

Materials

Materials selected with thought given to reducing their impacts over their life

Ecology

Land used for building improved by project

Team

Pidcock Architecture & Sustainability in association with the Office of Design (Charles Sturt University) and CN Walton & Associates

Caroline Pidcock

David Rudder

Tomoko Suga

Clark Walton

Abhay Kulkarni

Ed Kelly

Environmental Consultants: Advanced Environmental Concepts

Civil, Hydraulic + Structural Engineers: ACOR Consulting

Electrical + Mechanical Engineers: Lincolne Scott

BCA Consultant: Trevor Howse & Associates

Quantity Surveyors: Bayley Davies Quantity Surveyors